Herbs of Heritage: Ethnobotany in Irish Folklore

(Through March 2025)

The Marvin Samson Museum for the History of Pharmacy invites you to delve into the rich history of traditional Irish folk medicine. Featuring a selection of botanical specimens from the Museum collection alongside archival reproductions from the National Folklore Collection of Ireland, the display offers a glimpse of cures and remedies that have been passed down through generations in rural Ireland.

Established in 1935 by the Irish Folklore Commission, the National Folklore Collection is one of the world's largest folklore repositories. It captures Ireland's oral traditions, customs, and beliefs through a rich compilation of manuscripts, audio recordings, and photographs collected by folklorists, teachers, and students. The hand-written archival reproductions displayed here discuss remedies, cures, and healing properties attributed to various plants in rural Irish healing traditions. Some of these practices have even been scientifically validated, demonstrating the wisdom inherent in folk medicine.

The selection of newspaper reproductions also on display speaks to the intriguing intersection between rural Irish folk medicine and fairy folklore, in which sudden or unexplained illnesses and deformities were often attributed to fairy afflictions. People often resorted to using potent, and sometimes poisonous, plants to banish the changeling and cure the afflicted. The stories told in these newspaper archives document instances of real-life individuals who turned to these drastic ‘cures,’ often with fatal results. These historical accounts, viewed through the lens of modern medical knowledge, reveal a deep misunderstanding of conditions now recognized as medical ailments. An empathetic reading of these narratives grounded in an understanding of the state of medical knowledge and cultural beliefs of the time is crucial.

By presenting this nuanced narrative, "Herbs of Heritage: Ethnobotany in Irish Folklore" showcases the interdisciplinary nature of traditional medicine. It bridges the gap between ethnobotany, folklore, and medical history, offering a comprehensive understanding of how health and disease were perceived and treated in rural Ireland.

Herbs of Heritage: entire display, installation view

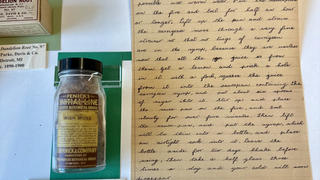

Herbs of Heritage: dandelion root, Irish moss, and selected NFCS entry

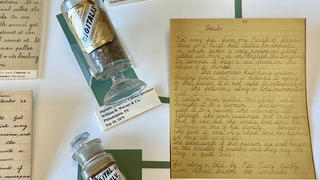

Herbs of Heritage: selection of belladonna specimens and NFCS entries, case detail

Herb of Heritage: side view of the display, installation view

Herbs of Heritage: side of the display, installation view

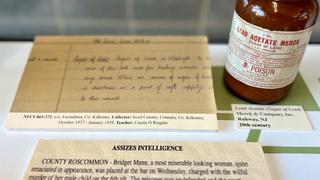

Herbs of Heritage: lead acetate Merck and NFCS entry

Herbs of Heritage: selection of digitalis specimens, lantern slide, and NFCS entries

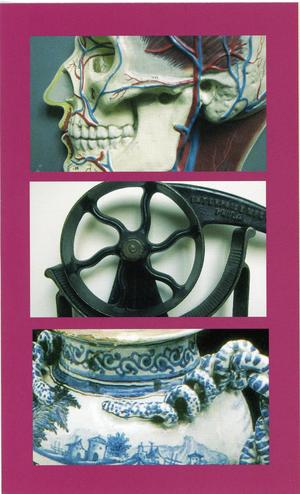

Selections from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy Permanent Collection

(September 6-December 19, 2024)

Museum Gallery, Griffith Hall First Floor

Exhibition sections:

Material History from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy

Artifacts and ephemera showcasing institutional history and student life at the college, including a special selection from the life and work of William Procter Jr.

Pharmacy Practice

History and modernity blend to offer an enlightening journey through the evolution of pharmacy care.

Includes fall 2023 student interns Dee Feuda and Deryn Bullock’s co-curated display on sex and gender in pharmacy products and spring 2024 student intern Maximus Fisher’s independent project, “Prescribing Trust,” an installation exploring the social contract between patients and pharmaceutical professionals within the evolving legal and cultural landscape of pharmaceutical advertising.

“Philadelphiana”

Highlights from Philadelphia's history of independent pharmacy practice and pharmaceutical manufacturing, illustrating the evolution from small-scale operations to corporate production.

Compounding & Manufacture

Tools and techniques of pharmaceutical production from pre-industrial practices to the present. Includes spring 2024 student intern Katherine Field’s independent project: “What is Drug Compounding? Selections from a Mallinckrodt Chemical Compounding Set,” fall 2022 student intern Sophie Vo’s display of pre-industrial pill-making hand tools, lantern slides showing early 20th century Pfizer and Lilly factories, and selections from the Alan Strauss global mortar and pestle collection.

Pharmacy Education

Lab samples and student notebooks bridge theory with hands-on experience.

Includes a selection of artifacts and ephemera from Joseph P. Remington’s (1847-1918) tenure at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, an extensive collection of traditional Chinese medicine cabinet specimens given to the PCPS Practice Department from Philadelphia’s Drueding brothers, and spring 2023 student intern Tanner Lamoreaux’s independent project on pharmacy education outside the university in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Natural Medicine

Botanicals, minerals, and other naturally-derived therapeutics used in healing practices and drug development across the globe. Includes a display on Ayurveda, one of the world's oldest holistic healing systems, as well as botanical specimens from the private collections of renowned botanist and pharmacist John M. Maisch and distinguished pharmacist and scholar Edson S. Bastin, both professors of materia medica at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy in the late 1800s.

Decorative Arts in Apothecary

European apothecary jars and albarelli, dating back to the 16th century offer insight into the utilization of herbs and substances in ancient medicine, while the series of Burroughs Wellcome Co. Delft tiles commissioned in the 1970s also on view demonstrate the prevailing power of apothecary iconography.

Material History from PCP: Women of the Class of 1916, glass lantern slide, on loan from the Joseph W. England Library and Archives

Pharmacy Practice: A Selected History of Narcotics, installation view

"Philadelphiana": city of Philadelphia map illustrating locations of drug stores and pharmaceutical manufacturing from the mid-18th to late-20th centuries, installation view

Compounding and Manufacture: glass lantern slides depicting industrial pharmaceutical manufacturing equipment at the Eli Lilly & Company plant from 1913-1919, installation view

Pharmacy Education: early-to mid-20th century Chinese medicine botanical specimens from the Dreuding Collection, installation view

Natural Medicine: Muscovite Mineral Sample, case detail

Decorative Arts in Apothecary: selection of 17th through 19th century Spanish and Italian albarelli from the Dr. David Costello Collection, installation view

Wyeth: A History Through Artifacts

(February 20, 2014 – October 2, 2015)

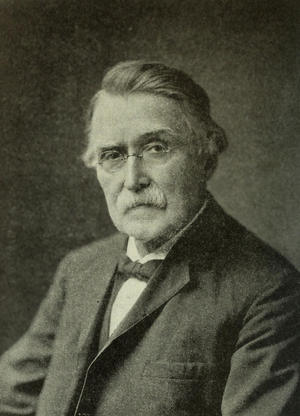

This exhibition celebrated the legacy of John Wyeth (1834–1907), a graduate of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, who in 1860 founded, with his brother Frank, a drugstore with a research lab that eventually grew to become the renowned, multinational pharmaceutical corporation, Wyeth.

The over 300 objects on display told a rich story of innovation and keen business acumen. They documented Wyeth’s humble beginnings and steady expansion over the company’s first few decades — a growth due to several key factors: the firm’s improvements to the taste of pharmaceutical products; its preparation of various compounds in advance and in large batches; the securement a government contract during the Civil War; and the invention of a machine for making tablets from medicinal powders, which allowed mass production of pills with pre-measured dosages. Among the “firsts” attributed to Wyeth in these early years are elixirs, compressed tablets, sugar-coated tablets, glycerin suppositories, effervescent salts and soluble gelatin capsules.

The objects in the exhibition illustrated distinct moments in Wyeth’s complex 150-year history, and they consisted of various categories of artifacts: manuscripts (ledgers, letters, records), ephemera, advertisements, prints and photographs, books, periodicals, devices, drug bottles, containers and packaging. These items represented a limited sampling of the large historical archive that Wyeth employees carefully (and proudly) assembled over many years. With the aim of preserving this important collection in perpetuity, Wyeth generously donated their archive to USciences in 2009.

Portrait of John Wyeth (left) and a picture of a bottle of aspirin manufactured by John Wyeth & Brother (right)

John Wyeth & Brother manufacturing plant, 11th St. & Washington Ave., Philadelphia; illustration reproduced from a 19th-century photograph

Small glass dish (or ashtray) with the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates and the Wyeth Logo (left) and Wyeth rotary tablet press, 1890s, height about 40” (right)

More Information About Wyeth

-

1834: John Wyeth is born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

1854: John Wyeth graduates from Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (PCP) with a thesis on the properties of Gillenia trifoliata (Bowman's Root)

1858: John Wyeth becomes the business partner of Henry C. Blair, in whose pharmacy he had served for five years

1860: John Wyeth and brother Frank establish their drug store at 1412 Walnut St, Philadelphia (where the Hyatt at the Bellevue now stands); above their retail store is the firm's lab and manufacturing space

1862: Wyeth's first catalogue is printed; it lists four pages of chemicals, crude drugs, extracts, fluid extracts. wines, and medicinal Liquors

1862: Sadie Wyeth (née Stewart), John's wife, gives birth to Stuart, their only child

1864: Wyeth begins supplying medicines and beef extract to the Union army during the Civil War

1866: Edward T. Dobbins, also a PCP graduate, becomes a Wyeth partner; subsequently the retail operation is sold to Frank Morgan, and the brothers confine their business to manufacturing and wholesaling

1872: Wyeth employee Henry Bower develops one of the first rotary compressed tablet machines

1876: Wyeth exhibits a wide variety of medicated suppositories at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and wins four awards

1883: Wyeth opens its first international facility in Montreal, Canada, and begins vaccine production

1880: A fire consumes two of Wyeth's three manufacturing buildings; Wyeth purchases a large, new property at 11th Street and Washington Avenue

1899: The company incorporates under the name John Wyeth & Brother, Inc.

1901: Wyeth, Inc. privately publishes An Epitome of Therapeutics, with Special Reference to the Laboratory Products of John Wyeth & Brother Incorporated

1907: John Wyeth dies at age 73 and is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia; John's son Stuart, a lawyer, becomes the titular head of the company; Frank Wyeth serves as vice-president until his own death in 1913

1929: Stuart Wyeth dies and leaves his controlling interest (55%) in the laboratory to Harvard University, his alma mater

1932: American Home Products (AHP) acquires Wyeth from Harvard for $2.9 million

1935: Alvin G. Brush becomes CEO of AHP, Wyeth's parent company; under his leadership, AHP acquires 34 companies in eight years; over the next few decades, AHP expands into a conglomerate that includes health care, food and household-product divisions

1938: AHP acquires SMA Corp., a producer of infant foods and vitamins

1941: The U.S. enters World War Il and Wyeth ships typical wartime drugs such as sulfa bacteriostatics, blood plasma, typhus vaccine, quinine and atabrine tablets; Wyeth is later rewarded for its contribution to the war effort

1942: Wyeth begins producing penicillin and very quickly becomes a main producer of the antibiotic

1943: Wyeth merges with Ayerst, McKenna and Harrison, Ltd. of Canada

1960s: Wyeth becomes a leading U.S. vaccine producer after supplying polio vaccine for Salk trials; the corporate headquarters is moved to Radnor/St. Davids, Pennsylvania, where it remained until 2003

1967: The WHO approaches Wyeth to develop a better injection system for smallpox vaccines; Wyeth waives patent royalties on its innovative bifurcated needle, aiding in the delivery of over 200 million smallpox vaccines per year

1984: Wyeth introduces Advil®, the first nonprescription ibuprofen in the U.S.

1987: Wyeth and Ayerst merge to form the prescription drug-based Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories

1989: AHP purchases A. H. Robins Co., makers of Robitussin®, ChapStick®, and Dimetapp®; in the late 1980s Wyeth acquires the animal health businesses of Bristol-Myers and Parke-Davis

1993: Wyeth introduces Effexor®, the first serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), for the treatment of clinical depression

1993: Wyeth founds the Women's Health Research Institute, the only institute in the pharmaceutical industry entirely dedicated to research in women's health

1994: Wyeth acquires American Cyanamid and its subsidiary Lederle Laboratories; this acquisition includes Centrum®, the leading US multivitamin

1995: Wyeth's sales top $13 billion

1997: The estrogen drug Premarin® becomes Wyeth's first brand to reach yearly sales of $1 billion

1997: Wyeth withdraws from the market its controversial diet drug fenfluramine after reports of deaths and other health problems associated with the drug combination known as fen-phen

1998: SmithKline Beecham backs out of an estimated $70 billion merger with AHP (SmithKline instead merges with Glaxo Wellcome in 2000, thus creating the world's largest drug company at that time)

2002: AHP changes its name to Wyeth

2003: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals establishes its global headquarters in Collegeville, Pennsylvania

2009: Pfizer, one of the world's largest pharmaceutical companies, acquires Wyeth for $68 billion; the Wyeth name continues in various business units

-

- The development of the “compressed pill” or tablet and the first rotary tablet press

- The first glycerin suppositories made in the U.S.

- The pioneering development of an infant formula patterned after mother’s milk

- The first orally active estrogen (Premarin®), which became the pioneer product for estrogen replacement therapy

- The first firm to produce penicillin commercially

- The first oral form of live trivalent poliovirus vaccine in the U.S.

- The development of a heat-stable, freeze-dried vaccine and the bifurcated needle, which led to the worldwide eradication of smallpox

- The first commercial synthesis of steroids for oral contraceptives

- The first Haemophilus b conjugate vaccine licensed for use in infants in the U.S. for protection against bacterial meningitis

- The first diphtheria/tetanus/acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine available in the U.S.

- The first serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for effective treatment of depression (Effexor®)

- The first combination estrogen/progestin hormone therapy in a single-tablet regimen

- The first in a new class of rheumatoid arthritis drugs known as biologic response modifiers

- The first albumin-free formulated recombinant factor VIII product

- The first vaccine for the prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease in infants and toddlers

- The first antidepressant indicated for generalized anxiety disorder

- The first targeted chemotherapy agent using monoclonal antibody technology

- The first to market an OTC ibuprofen product (Advil®)

- The first canine heartworm preventative that provides six months of continuous protection in one injectable dose

- The first canine Lyme disease and Lyme combination vaccines

- The first molecular cloned feline leukemia vaccine

- The first modified-live canine parvovirus vaccine

- The first West Nile virus vaccine for horses

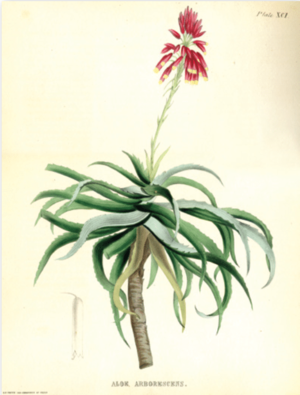

Botanicals to Braque: Five Centuries of the Illustrated Book

(March 22, 2012 – May 31, 2013)

This exhibition was a historical survey of prints — primarily woodcuts, engravings and lithographs — used in book illustration from about 1480 to about 1965. It included notable loans from the USciences Rare Book Collection, which was rich in illustrated herbals and titles related to the practice and history of pharmacy. A highlight of these holdings is Vegetable materia medica of the United States (first published in 1818) by renowned 19th-century botanist W.P.C. Barton; the University owned, remarkably, twenty original copper engraving plates used to create the illustrations in this text, two of which were on display here, alongside the hand-colored prints produced from them. Rounding out the selections was a diverse assemblage of more than 60 book illustrations spanning five centuries; most were loans from private collectors, and they marked the first appearance on campus of original graphic art by acknowledged giants of Modernism such as Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Chagall, Gauguin and Miró.

History of the Illustrated Book

-

Prior to the mid-15th century, the European concept of "book" consisted of bound manuscripts, laboriously produced by scribes — often monks — and sometimes also illustrated (or "illuminated") in color by artists who specialized in miniature painting. In the 1450s, however, a revolution occurred: The introduction and exploitation of moveable type (already in use for centuries in the East), made famous by Johann Gutenberg, a printer from Mainz, whose typeset and printing processes allowed identical books to be produced in great numbers and more inexpensively than manuscripts. Within a short period books began to be illustrated with woodcuts — the product of a design carved in relief into a block of wood. These printed images appeared alongside or were integrated into the text, and their function was to supplement, clarify or structure the text. Because both block and type were relief processes (i.e. with a raised printing surface) the woodblock could be made the same thickness as the height of the type, and the printer could generate a page with text and illustration in one step.

Early books, called "incunabula" if published before 1501, were instrumental in the dissemination of religious and profane images, and sometimes their illustrations were crudely hand-colored. (A rare example of this was on display in the exhibition.) As Europe emerged from the pious Middle Ages and the tastes of a burgeoning middle class turned increasingly from heavenly to earthly themes, more secular subjects appeared on woodcuts, and over time these rather naïve compositions gave way to more sophisticated designs. Herbals, travel books, stories of love and passion, fables and legends and historical events became popular with the masses.

-

In Germany, the major print and book centers included Cologne, Ulm, Nuremberg, and Augsburg; the latter is perhaps where the first illustrated Bible was issued, the Biblia sacra germanica (c. 1475), printed not in Latin but in the vernacular, or spoken tongue. The publisher Anton Koberger was responsible for one of the greatest publishing ventures of his time, the celebrated folio Weltchronik (or Nuremberg Chronicle) of 1493: Over 1,800 illustrations were provided by skillful repeated use of 646 woodcuts of Old Testament and historical figures, cities and events, cut by a team of artists headed by Michel Wolgemut, and assisted by his young pupil, the soon-to-be-famous Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).

-

In Italy, book presses — many of which were established by itinerant German printers — began springing up in the 1460s, with Venice being the most important center. Reflecting the renewed interest in classical antiquity and humanism, editions of Cicero, Pliny and Augustine were particularly popular. With its bestiary of freaks and abnormalities, Pliny’s encyclopedic Natural History (a 1519 edition of which was on view in the gallery) was responsible for future flights of fancy in many illustrated books of the period. It was in Venice in 1490 that Aldus Manutius founded the first publishing "conglomerate," which produced books of surpassing beauty by engaging the finest scholars of the age and a staff of experienced painters. His Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a monk’s romantic tale of passion, is still considered the ultimate in perfection of printing, illustration and typographic design. (One of Aldus’s most handsome and readable typefaces, revived in the 20th century and named "Bembo" for the renaissance scholar Pietro Bembo, is still used extensively today.)

It is notable that the great majority of book illustrations — including the herbals and anatomical prints that were on view in the exhibition — served the needs of an employer or specialized community, and these pictures therefore came into existence as conveyors of information or opinion rather than as expressions of an illustrator’s personality or as works of art. This fact, however, has not precluded modern specialists from designating the finest of these printing and illustrating ventures as artistic tours de force.

Pharmaceutical theatre, wood engraving, in Antonio de Sgobbis, Nuovo, et ubiversale theatro farmaceutico: fonato sopra le preparation farmaceutiche scritte da’ medici antichi, ... Venice, 1667, title page (left) and Distillation apparatuses, hand-colored woodcut, in Johannes von Cuba and Eucharius Rösslin, Kreuterbuch: von natürlichem Nutz, und gründtlichem Gebrauch der Kreutter, ..., Frankfurt am Main, 1550, p.V verso (right)

Paul Gauguin, two woodcuts for the book project Noa Noa (Fragrance, Fragrance): Auti Te Pape (Women at the River) and Te Po (The Night), designed 1893-94 (left) and Georges Braque, still life with fruit, signed lithograph from Kronenhalle, 1862- 1922-1962, edited by Manuel Gasser, Zurich and Paris, 1962 (right)

Human skull, wood engraving, in Henry H. Smith, M.D., Anatomical atlas, illustrative of the structure of the human body, Philadelphia, 1859, frontispiece (left) and Joan Miró, figure with a star, lithograph from Tristan Tzara, Parler Seul, Paris,1948-50 (right)

The art of engraving or incising into metal dates to antiquity, but the idea of using engraved plates to create prints can be traced to goldsmiths in 15th-century Germany. Various prominent German and Italian renaissance artists produced designs for woodcuts and engravings, among which Dürer is perhaps best known. (It is still hotly debated whether or not Dürer cut some of his own blocks before the guild of form cutters had become officially entrenched in 1498, and before increasingly large commissions made professional help necessary.) The additional example of Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) — best known for his Primavera and Birth of Venus — who designed engraved illustrations for a 1481 edition of Dante’s Inferno, demonstrates that major Renaissance painters (with no loss to their egos) were commonly engaged in creating designs for the so-called "minor" arts such as metalwork, ceramics, and books. By the early 17th century, engraving had ousted woodcut as the preferred method of book illustration in Europe.

Writing about the social importance of print techniques, William Ivins Jr, Curator of Prints of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, observed in 1943:

It can be reasonably argued that the great event of the fifteenth century was not the rediscovery of Greek or any other sort of ancient learning, but the discovery of mechanical ways to make pictorial records in duplicate, exactly, cheaply, and in vast quantities. This discovery made it possible for the first time to make pictorial statements and records in exact duplicates and to distribute them in invariant visual form simultaneously to many different people in many different places. The importance of this to human society can hardly be overstated. It has possibly had greater effects than any mechanical discovery since the invention of writing, as it is basic not only to our knowledge of the past and the present, but to a very large number of our modern technological and scientific developments.

One could persuasively argue that from the time of their invention the electric photocopier, printer, personal computer, and the internet have had a greater and more pervasive effect on the dissemination of knowledge and images than traditional printmaking methods; but for the 500 or so years leading up to those landmark developments, and in an ever-increasingly visual culture, the print reigned supreme, for it brought to life the worlds of ideas and imagination presented in a wide variety of scientific, literary, and artistic texts.

Secundum Artem: Selected works of art and design from the University collections

(November 11, 2009 – May 27, 2011)

A Latin phrase literally meaning “according to the art or practice,” secundum artem often refers to doing something in the accepted manner of a skill or trade. In medicine, it can mean “employing skill and judgment” or “to make favorably with skill." In pharmacy, preparations made secundum artem ensure they are pure and unadulterated, but the phrase also encompasses the apothecary’s obligation to provide good advice to customers who request over the counter drugs.

Through the display of over 100 objects related to the history of pharmacy and science, this exhibition explored the products of various skilled scientists, artists, craftsmen and designers active primarily in Europe and the United States during the last 300 years. What links these objects is that they were manufactured according to the specific art or practice, or secundum artem, of their makers. The wide media — prints, photographs, manuscripts, paintings, ceramics, glass, wood and metal — and categories of objects — instruments, advertising and packaging, natural science, etc. — attest to the broad holdings of the Marvin Samson Center for the History of Pharmacy. In each instance, an object was conceived with a particular function in mind, which ranged from the purely utilitarian to the purely decorative, but very often with the boundary between the two being blurred.

Frequently an object’s elegant design or the addition of applied decoration is sufficient to elevate it to the status of veritable art object. The 1930s Remington typewriter that was on display in the gallery is an example of the former: a well-thought-out and restrained form in keeping with the philosophy expressed by Camillo Olivetti, a designer at one of Remington’s competing firms, who remarked “a typewriter should not be a gewgaw for the drawing room, ornate or in questionable taste. It should have an appearance that is serious and elegant at the same time.” At the other end of the spectrum is the pair of late-17th-century Italian blue-and-white ceramic apothecary jars. Ostensibly made as containers for the drugs named on their labels (theriaca and hyacinth), their large, bold form (with twisted snake handles) and finely-painted decoration eclipse their utilitarian function and thus distinguish them as notable works of ceramic art.

The significance of a sizable group of objects in the exhibition lies with their didactic function. For example, the twelve late-19th-century German botanical panels displayed in the galley niches were produced as teaching aids, but their appeal and interest today as artistic prints is undeniable. In a similar way, our interest in crystal and rock specimens and in animal skeletons goes beyond their classification as, respectively, accidental products of geologic activity or products of evolutionary biology: They are examples of nature as art and as good design.

To be sure, many of the innovative art movements of the 20th century resulted in a redefining or broadening of what constitutes “art.” (One need only think of Marcel Duchamp’s Dadaist “ready mades” of the 1910s, Jackson Pollack’s drip paintings of the 1950s, or Andy Warhol’s Pop Art creations of the 1960s and 70s.) Visitors to this exhibition were invited to view in new light a series of diverse artifacts made secundum artem and (primarily) for utilitarian purposes, to discover how, beyond their value as historical documents, such products of creative minds relate and compare to standard and accepted concepts of the art object. What makes an object beautiful? How can design transcend function?

Frederick Gutekunst and the Art of Photography

(April 29, 2008 – September 29, 2008)

Frederick Gutekunst, the son of a German émigré cabinetmaker, was born in the Germantown section of Philadelphia in 1831. From age 12 to 18, at his father’s urging, he apprenticed in the law office of Joseph Simon Cohen, prothonotary to the Supreme Court. Law proved so “dry and uninteresting” to Frederick that — as he recounted later in life — he would spend the majority of his dinner allowance on materials to carry out experiments in physics and chemistry. It was around this time that he developed an interest in photography, a new and burgeoning art form that would eventually make him famous. (As if somehow a portent of his natural talent, the name “Gutekunst” translates from the German as “good art.”)

In his early teens Frederick was a frequent (volunteer) sitter at the daguerreotype gallery of Marcus Aurelius Root, who was among the earliest photographers in America; however, Frederick learned the craft of daguerreotyping from Robert Cornelius, founder, in 1840, of Philadelphia’s first photographic studio. Although not its originator, Frederick succeeded in the chemical process that converted the unique daguerreotype image into a printable electrotype (intaglio) plate; the results were promising, but not good enough to pursue commercially. Frederick’s talent for chemistry did not go unnoticed by his father, who apprenticed him, from age 18, to the druggist Frederick Klett, which soon set him on a path to Philadelphia College of Pharmacy (PCP). It is perhaps no coincidence that Cornelius studied chemistry with Gerard Troost, PCP’s first chemistry professor.

In 1853, after a four-year apprenticeship with Klett, the last two of which included simultaneous matriculation at PCP, Frederick graduated with a thesis titled "History of electro-metallurgy and its application to pharmacy." As Frederick progressed towards a pharmacy career, he also began experimenting with his first camera, which consisted of a five-dollar lens he added to a box built by his father. In October of that same year, at age 22, he entered his first photography contest at the 23rd Exhibition of American Manufacturers at the Franklin Institute for the Promotion of Mechanical Arts.

For the next two years Frederick worked in the Market Street drug store of Avery Tobey, a fellow PCP alumnus. Meanwhile, Frederick’s interest in photography grew even stronger through the encouragement of his younger brother Louis, a barber, with whose financial support Frederick opened, in 1856, the “Gutekunst & Brother” photography studio at 706 Arch Street. Their partnership lasted until 1860, when Louis resumed his former work.

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 and Philadelphia’s importance as an economic, industrial and military center turned Gutekunst’s studio into a major photography destination, particularly for portraiture. In 1866, the business moved several doors down to 712 Arch Street, and Frederick spared no expense turning the larger space into a “temple of beauty and grandeur.” As one newspaper columnist wrote in a 1913 profile about him: “There was hardly a busier man in

Philadelphia than Mr. Gutekunst. As the troops tramped through the city, thousands of men flocked to his Arch Street studio to procure a likeness to send back to loved ones left behind, and many times those curious little prints were, and still are, the only pictures of tangible kind of this or that boy who marched away from home in Federal blue. The generals came, Grant and Meade and Sheridan while, as his reputation spread, the most prominent figures in other walks of life

more and more frequented the photographer’s studio.”

Gutekunst was a favorite photographer of the elite of the period, and his sitters included Walt Whitman, Ulysses S. Grant, Lucretia Mott, Thomas Eakins, A. J. Drexel, John D. Lankenau and Woodrow Wilson. The nine national and international exhibitions the studio participated in between 1865 and 1876 garnered it gifts, medals, and awards, all of which helped secure for Gutekunst a name beyond the United States. One of the studio’s most celebrated images is an impressive technical feat: a ten-foot long panoramic view of the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, which at its unveiling in 1876 was described as the largest photograph in the world. (One of several rare surviving original imprints of this subject was on view in this gallery.)

Photographs taken by Frederick Gutekunst of Ulysses S. Grant (left) and Walt Whitman (right)

Photographs taken by Frederick Gutekunst of William Procter Jr. (left) and Joseph P. Remington (right)

Photographs taken by Frederick Gutekunst of John M. Maisch (left) and Susan Hayhurst (right)

Throughout his more than 60-year career Gutekunst maintained close ties with PCP. He was an active member of the Alumni Association, a significant donor, and his photographs appeared regularly in PCP publications. Assembled in several albums still owned by USP (two of which were on display in this gallery) are dozens of photos of PCP graduates, officers, and trustees that bear the Gutekunst studio stamp. At Gutekunst’s death in 1917 the American Journal of

Pharmacy published a three-page obituary, and the PCP Board of Trustees issued the following resolution to memorialize him:

Whereas the membership of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy has suffered a severe loss by the death of Frederick Gutekunst, one of the oldest graduates, and an honorary member of the College, and whereas the membership of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy wishes to express

sorrow in the loss of an esteemed and beloved member who by his long and eventful life, devoted to the Art of Photography, won the title of ‘Dean of American Photographers.’Be it resolved that in the death of Frederick Gutekunst the membership of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy has lost one of its most distinguished associates who endeared himself by his many gifts of portraits of living, and reproductions of portraits of deceased officers and members, and by his life-

long interest in all affairs of the Institution; also that by his skill in his Chosen Art he has inspired many others to attain the same perfection of work that was so characteristic of him, and thereby elevated the Art of Photography to so high a plane that his name will ever be an inspiration to those that follow his footsteps.

Circa 1821: Design and Material Culture in the Young Republic

(July 20, 2006 – September 28, 2007)

The first half of the 19th century is a particularly remarkable time in the history of the United States. For much of that period, the nation was a loose association of scattered states bordered by a vast wilderness to the west and miles of ocean to its east. On the political front, America fought the English in the War of 1812 — deemed our country’s “second war of independence” — only to be internally dissevered by the Civil War, starting in 1861; in between there were a handful of smaller but highly consequential territorial wars, mostly in the southern and southwestern portions of the nation.

Key Information Regarding the Early 19th Century in America

-

The Louisiana Purchase, in 1803, sparked interest in expansion to the west coast. A few weeks after the purchase, President Thomas Jefferson had Congress appropriate $2500, “to send intelligent officers with ten or twelve men, to explore even to the Western ocean.” Jefferson selected Captain Meriwether Lewis to lead the expedition, which later was known as the Corps of Discovery. Lewis selected William Clark as his partner, and their entire party consisted of approximately forty men.

The Corp’s historic journey began in May 1804, and during the next 28 months, they traversed over 8,000 miles. Less than one year into the expedition, the team had already reported the discovery of 108 botanical and 68 mineral specimens and produced Clark’s map of the United States. By expedition’s end in September 1806, they had recorded important information about the new territory and its Native American tribes, as well as the botany, geology and wildlife in the region.

-

In painting, the early 19th century was the great period of recording America. A string of English artists traveled to the young republic to paint views of cities, harbors, or notable estates and scenic spots in the countryside; they became known as “view painters,” and their activity gave impetus to an ambitious publication produced in Philadelphia in 1820–21. Picturesque Views of American Scenery was the result of a collaboration between two English artists and two American publishers, which culminated in a series of twenty superb hand-colored aquatints. Numerous other portfolios were published around this time in response to the growing interest in recording America. Motivated by the related desire to document and study the nation’s flora and fauna, French-born John James Audubon (1785–1851) had his drawings of birds engraved and published; the first volume of these landmarks in 19th-century natural history appeared in 1827.

-

The tremendous growth of the nation during the first half of the 19th century is reflected in the U.S. flag, which went through twelve design changes between 1795 and 1851, to accommodate the addition of eighteen states to the Union during that period. This growth prompted impressive transportation projects, most notably the Erie Canal. Completed in October 1825, the canal connected the Hudson River to Lake Erie, thus allowing New York to tap into the untold resources of the interior continent. New York became “the great commercial emporium of America,” and the success of the Erie Canal created a frenzy of canal building throughout the nation, which in turn spurred the growth of the steamboat industry. Meanwhile, land transportation was being revolutionized by the steam railroad to the extent that by the 1840s over nine thousand miles of track had been laid. This abundance of transportation routes allowed the nation to firmly bind its parts.

-

In the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, the United States had given notice to the European powers that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to colonization. In spite of America’s new political independence from Europe, its citizens continued to follow the fashions and designs that originated abroad. Far from being a remote outpost, the young republic had relatively quick access to new styles from London, Paris, and other European cities through imported goods, immigrant craftsmen who trained abroad, and design books and prints that were exported soon after their publication. By 1820, the table of any middle-class citizen could contain sugar from Cuba, fruits of the Mediterranean, pepper from Sumatra, coffee from Arabia and tea from China.

-

Early 19th-century artists and craftsmen in Europe and America had unprecedented access to the material culture of other times and places. Far-reaching archeological adventures, more extensive travel and trade about the globe and the proliferation of printed reports and reproductions all provided a rich and novel vocabulary of design drawn from ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, from the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the more recent European past. Artists used this wealth of fresh evidence with a freedom of expression that constituted a complex new language of styles — styles usually labeled as historical revivals but that tell us far more about the outlook of the 19th century than they do about any earlier times.

Wealthy Americans avidly participated in the tradition of the Grand Tour by embarking on extended tours of England and continental Europe; through these experiences and, more specifically, through the art and objects they acquired during their travels, they were able to find context and meaning for their lives by considering themselves heirs of the great Western traditions. A great sense of nationalism pervaded the country, and leaders in all fields looked to the classical past of Greece and Italy for forging the identity of their young democratic republic.

-

America’s hunt for models of design and ornament in the first decades of the century witnessed several versions of the neoclassical style, often marked by regional differences. Much of the furniture of this period echoed two earlier English trade catalogues, George Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788), and Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (1791–94). These design books, each with 19th-century editions, were largely responsible for disseminating neoclassicism throughout Europe and, slightly later, throughout America. Starting around 1815, American neoclassical design began to be influenced by Empire styles derived from pattern books, such as Percier and Fontaine’s Recueil de décorations intérieures (1801 and 1812), the first guide to Greek, Roman, and Egyptian designs based on archeological sources, and Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807). A more direct introduction of classical design came via French and English émigré artists working in America.

Detail of platter with View of the Dam and Waterworks at Fair Mount, Philadelphia; earthenware; England, Staffordshire, attributed to the Burslem pottery of Joseph Stubbs, c. 1825–30

Candlestick; sterling silver; Boston, Bigelow, Kennard & Company, c. 1845–60 (left) and Pharmacy jar inscribed "Beur: de Cacao"; porcelain; France, c. 1820–40 (right)

Armchair; mahogany wood; England or United States (perhaps Philadelphia), late Sheraton style, c. 1810–20 (left) and Cornucopia vase; colored glass and metal on a marble base; England, c. 1850 (right)

Receipt book, Philadelphia College of Pharmacy; Philadelphia, 1835–72 (left) and William R. Fisher (d. 1842); oil on canvas, artist unknown; probably Philadelphia, 19th century (right)

Designs after the antique; plates V, VI, XI, XIV, and XXI from Nuova raccolta rappresentante i costume religiosi, civili, e militari degli antichi Egiziani, Etruschi, Greci, e Romani; tratti dagli antichi monumenti, per uso de professori delle belle arti (plate XIV shown on left) engravings by Domenico Pronti Rome, 1808 and The Raving Maniac and the Driv’ling Fool; The Gin Palace; The Drunkard’s Home; and The Upas Tree etchings; designed by George Cruikshank London, 1842 (right)

As many of the objects that were in this exhibition attest, there was a constant exchange of ideas between artists designing in the fine arts (e.g., prints, painting, architecture) and those active in the applied arts (e.g., furniture, glass, metalwork, ceramics). Philadelphia was given special attention in the displays in part because it was the largest city, financial center, and major port in the country until around 1830, when that distinction passed to New York. But more importantly, for the period covered by the exhibition, Philadelphia was a city of firsts and of innovation and, in many respects, the vanguard of art, culture, politics and education for the fledgling republic.

Human/Humane: The BioArt of Frank H. Netter, M.D.

(April 22 – July 21, 2005)

Frank Henry Netter (1906–1991) studied at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students’ League, and by the mid-1920s, he was a successful commercial artist for publications such as The Saturday Evening Post and The New York Times. At his mother’s urging to follow a more "serious" career, he entered medical school at New York University, where he received his M.D. degree in 1931. During his student years, Netter’s notebook sketches caught the attention of various medical professors, allowing him to supplement his income by illustrating lectures, articles and textbooks. In private surgical practice he accepted art commissions, but eventually this artist-cum-surgeon gave up his medical practice altogether, in favor of a full-time commitment to art. The result was Netter’s legendary ability to comprehend thoroughly as a physician before liberating the potent creative forces of the artist.

As an army officer in WWII, he illustrated several manuals on first-aid for combat troops, sanitation in the field and survival in the tropics. In the late 1930s, shortly before his military duty, he had already begun a rewarding and prolific 45-year partnership with the Ciba Pharmaceutical Company (later Ciba-Geigy, which in 1996 became Novartis), which resulted in thousands of designs for the serial Clinical Symposia and what has become his opus magnum, The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations (13 volumes). The latter illustrates the most important systems and diseases of the body in painstaking, brilliant detail and remains one of the most famous medical works ever produced. Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy, first published in 1989 (and translated into eleven languages) presents anatomical paintings largely culled from The Ciba Collection and is currently the anatomy atlas of choice among medical and health professionals the world over. Nearly all the original works in the current exhibition originate from these published sources.

“I try to depict living patients whenever possible. After all, physicians do see patients, and we must remember we are treating whole human beings.”

– Frank H. Netter, M.D.

Although created for their intellectual content, Netter’s paintings are appreciated for their aesthetic qualities, such as their ability to depict the functionality of organs in a strikingly animated manner. Although the study of anatomy dates to the ancient Egyptians, the art of medical illustration did not truly emerge until the Renaissance, when artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo created drawings based on cadaveric dissections. The stringent clarity, stunning accuracy and beauty of the works of this ‘"Michelangelo of Medicine" — as a 1976 Saturday Evening Post article described Netter — follow solidly in the tradition of this marriage of science and art.

One of the most important blends of this tradition occurred in the 16th century, with the publication of De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543. A collaboration between the anatomist-physician Andreas Vesalius and the artist Jan Stefan van Kalkar of Flanders, De Fabrica was the standard anatomy atlas for centuries, to be enhanced or supplanted only when technological discoveries (such as the invention of the compound microscope in the 17th century, or the discovery of X-rays in the 19th century) revealed new knowledge about human anatomy. In the spirit of collaboration, it is useful to recall that although a physician/surgeon himself, Netter consulted dozens of medical experts throughout his career as he conceptualized his paintings. This is especially true for design projects documenting new discoveries in medicine, such as computerized axial tomography (CAT) scanners, joint replacements and the first artificial heart transplant.

“[My work] deals with the most humanistic, the most soul-searching of subjects...people break bones, develop painful or swollen joints, are handicapped...some are beset by tumors or undergo amputations. These are people we see about quite commonly and are often our friends, relatives, or acquaintances.”

– Frank H. Netter, M.D.

Always drawn to the complexity and diversity of people, Netter strived to create faces and bodies in his work that mirrored their individual personalities. The result was that disease and trauma are viewed humanely, that is, as a complex life challenge faced by people rather than an isolated intellectual puzzle. Netter’s sense of humanity and empathy for patients is one of the most distinguishing features of his paintings; as he said, “I always tried to make [the subject] look like a living patient, with proper facial expression and so forth, to show that this is not a machine we are dealing with. We’re not repairing a television set when we’re treating these patients.”

Netter spent far more time researching a subject and planning an illustration than in executing it. After absorbing from a multitude of sources as much information as necessary, he typically created pencil sketches, which were then copied and transformed into finished designs in gouache — a watercolor technique — to which he often added opaque paints, colored pencils or pastels, for shading and fine detail. Nearly half of the works in the current exhibition appear with their Mylar overlays which contain text and additional graphics that supplemented or completed the paintings in their final, printed form.

Grinding Stone to Art Object: The Mortar and Pestle from the Renaissance to the Present

(December 9, 2004 – December 2, 2005)

The venue for this private exhibition was Wyeth Pharmaceuticals in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. This exhibition featured a selection of some of the most interesting mortar and pestle sets from the museum's collections. With thirty-one examples from over a dozen countries, and in materials such as stone, metal, wood, glass, ceramic and ivory, the exhibition attested to the astounding diversity these objects have displayed over the past 450 years.

Of all the articles comprising the pharmacist's armamentarium, mortars and pestles hold a place of honor as the indispensable, and therefore most characteristic tools of the profession. Since written history began, their association with pharmacy has been so intimate that they have become emblematic of the apothecary's art. They were probably the earliest implements used in the practice of pharmacy and medicine as well as in the preparation of food by primitive man. The antiquity of these devices is well documented in early writings, such as the Egyptian "Papyrus Ebers" of c. 1550 B.C.E. (the oldest preserved medical manuscript) and the Old Testament (Numbers 11:8 and Proverbs 27:22).

Whether improvised from nature to be used primarily as grinding stones or designed, fabricated, and decorated to a degree that merits status as veritable art objects, mortars are found in every corner of the earth. Their users include members of isolated tribes, professional and household cooks, students, scientists and pharmacists. At least two mortars on display have specialized functions in food preparation: the Mexican example, formed from volcanic rock, whose rough composition excels at cutting and grinding chili or red pepper; and the highly decorative Near Eastern wooden example, with a tall and narrow inner cavity specifically designed for crushing coffee beans. The centerpiece of the exhibition, a large brass mortar dated 1767, bears the imperial monogram of Frederick the Great, and was almost certainly used by the king's personal apothecary.

Eclectic Road to Health

(October 2001 – March 14, 2005)

Did you know that in 1892, herbal remedies such as St. John's wort, saw palmetto and valerian were used? In the year 2000, these same remedies were among the top ten best sellers. What explains this staying power? What constitutes "alternative" medical treatment? How do treatments outside the realm of physician-directed programs gain acceptance in "mainstream" medicine?

How does culture influence health care? Medical systems such as traditional Chinese, Ayurvedic and folk medicine offer very different cultural views of medicine. By using an approach that integrates lifestyle and health, these systems offer us an alternative view of therapeutics.

This exhibition addressed these issues in a journey through the history and development of unorthodox medical treatment. From bloodletting with leeches to healing with plants, the exhibit examined the historical use of "alternative" therapeutics, the evolution of complementary treatments, specific types of treatment and the extensive amount of research being conducted today.

African Mortar and Pestle (left) and Home Medical Book from 1917 in which Dr. Ritter offers therapeutic options for home use including traditional, homeopathic and "folk" remedies (right)

Chinese medicine objects (left): Traditional Chinese medicine uses a variety of materials including herbs, minerals and insects in its prescriptions. Ayurvedic health charm (right): Ayurvedic medicine from India has lasted for thousands of years and Western medicine has begun to take notice.

Print of the herb, dioscorea villosa (wild yam), often used by eclectics, from an 1892 American herbal medicine book (left) and a homeopathic medicine case, circa 1870s (right)

Honey, aloe and leech apothecary jars (left): Older apothecary jars show that popular current remedies such as honey and aloe have earlier uses; leeches have been rediscovered for the anticoagulant properties of their saliva. And wine and gin labels (right): In America, pharmacies were preparing prescriptions using various forms of alcohol into the twentieth century.

Capsicum Plaster advertisement from 1880 (left): Capsicum, hot pepper, has been a popular remedy for centuries, taken orally or applied as a plaster. An ad for Eli Lilly & Co. Experimental Farm (middle): Pharmaceutical companies have been growing and harvesting medicinal plants for a long time. Today the chemical composition of the plant's active components are often replicated as a synthetic which can be patented. Cadbury Cocoa advertisement (right): In the past, chocolate was used to strengthen the system. Today we know it contains the same antioxidants as green tea.

Think that the current craze for health and fitness is new? Take a look at some of the popular magazines from another era: an 1886 ad touts Gettysburg Spring Co. Kata lysine water, a 1910 cover of Physical Culture Magazine boasts a "Turkish bath in your home.”

The Influence of Non-conventional Approaches to Healing

-

Native American materia medica

Botanical movements

Homeopathy

Osteopathy

Naturopathy

Chiropractic

Hydropathy

Traditional Chinese medicine

Ayurvedic medicine

-

Bernarr MacFadden, leader of the Physical Culture Movement, who first encouraged women to exercise and eat well

Jack Lalanne, disciple of the Physical Culture Movement, precursor to the Aerobic and Physical Fitness Movement

The Kellogg brothers, who developed peanut butter, granola and toasted flakes, and whose obsession with the bowel made "colonic cleansing" a national passion

Samuel Thomson, the early 1800s self-taught botanical practitioner whose patented system of medicine was the first significant challenge to orthodox medicine in America

John Borneman, whose homeopathic pharmacy gave rise to a modern day industry

Included in the exhibition were sections on:

- Historical perspectives of Integrative medicine and the use of "botanical drugs," including herbal specimens, advertisements and products

- Alternative movements developed in the 19th century such as Thomsonian Botanics, hydropathy, naturopathy, eclecticism, chiropractic, osteopathy, homeopathy and physical culture.

- Traditional systems of medicine such as Chinese, Ayurvedic and folk medicine

- Food therapeutics, including nutraceuticals, "super" foods and supplementation

From Panacea to Science: 175 Years of Pharmacy in Philadelphia

(Ended Spring 2001)

The exhibition exemplified the importance of the USP's role in the formation of pharmacy as a profession. The exhibition contained artifacts and documents relating to the University's long history of influence on the field of pharmacy; the founding of Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.

It included:

- A timeline, "Behind and Over the Counter," of pharmaceutical development from 1821 (the date of Philadelphia College of Pharmacy's inception) to the present

- Famous alumni of the University such as Eli Lilly, Josiah K. Lilly, Gerald F. Rorer, William R. Warner, Robert McNeil, John Wyeth, Silas M. Burroughs and Sire Henry S. Wellcome, who have vastly contributed to the evolution of American pharmacy

- The development and changes affecting education in the health sciences

- The influence and development of pharmaceutical related industries in Philadelphia

- Patent medicine