The Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and the 1918 Influenza

Editor's note: This article was written prior to University of the Sciences' merger with and into Saint Joseph's University and does not reflect the current, combined institution. References to programs, offices, colleges, employees, etc., may be historical information.

As World War I reached its conclusion, a deadly strain of influenza reached Philadelphia’s Naval Shipyard. On September 28, 1918, hundreds of thousands of people flooded Broad Street for the Liberty Loans Parade, a super-spreader event that would transmit the “Spanish flu” across the city. Within 24 hours, hospital beds were full. More than 10,000 died in October alone.

As World War I reached its conclusion, a deadly strain of influenza reached Philadelphia’s Naval Shipyard. On September 28, 1918, hundreds of thousands of people flooded Broad Street for the Liberty Loans Parade, a super-spreader event that would transmit the “Spanish flu” across the city. Within 24 hours, hospital beds were full. More than 10,000 died in October alone.

When disaster struck, Philadelphia College of Pharmacy’s trustees jumped to action. The college was already involved in the war effort, training hospital corpsmen for the U.S. Navy, but now, an evolving public health emergency, meant the college must take on new responsibilities.

On October 1, 1918, Professor Julius W. Sturmer proposed the suspension of afternoon classes, “until the grippe epidemic had been brought under control.” This would help to mitigate “the desperate situation in many Philadelphia drug stores, where the dirth (sic) of trained help makes it difficult to supply the medicines now so badly needed.” The motion passed. Classes ended at noon.

The following day, the Inquirer reported that students of the College would “be given a chance to lend assistance to druggists of the city and vicinity.” According to a contemporary report from the National Association of Retail Druggists, the situation was dire.

The following day, the Inquirer reported that students of the College would “be given a chance to lend assistance to druggists of the city and vicinity.” According to a contemporary report from the National Association of Retail Druggists, the situation was dire.

“The epidemic of the Spanish influenza has made the retail druggists of Philadelphia work overtime to get out the prescription work. Many stores, being shorthanded, closed all other departments and confined their work to prescriptions only. The demand for certain drugs has practically depleted the stock of the wholesale druggists, and the retailers are experiencing hardships in securing the many drugs used in the compounding of prescriptions. In other words, the jobbers were swamped with orders, and many retailers were held up four and five hours waiting for their orders to be filled.”

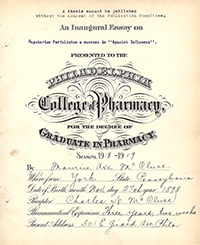

Later a graduate of the Class of 1919 remembered, “We who joined in P.C.P.’s forces were made to feel that we were able to render service probably equal to that of those engaged in actual warfare.”

Later a graduate of the Class of 1919 remembered, “We who joined in P.C.P.’s forces were made to feel that we were able to render service probably equal to that of those engaged in actual warfare.”

Another recorded his experiences in vivid prose: “The most conspicuous symptoms of ‘Spanish Influenza’ were the bursting headache, the soreness of the eyeballs and the teeth and the severe muscular pain, the profuse perspiration without the mitigation of the heat and catarrhal fever.”

A few weeks later, the trustees determined that afternoon classes would resume. Dean Charles LaWall commended students: “To those of our students who have nobly helped fight the battle against the influenza, the community is indebted, but like many other noble deeds in these times, the reward will mostly come in the consciousness of work well done and duty unshirked.”

To those of our students who have nobly helped fight the battle against the influenza, the community is indebted, but like many other noble deeds in these times, the reward will mostly come in the consciousness of work well done and duty unshirked.

Charles LaWall, Dean

A future president of the College, Wilmer Krusen, stood at the epicenter of the city’s response to the pandemic. Krusen, an obstetrician, had been named Philadelphia Public Health Commissioner in 1916. An innovative and energetic public health official, he opened emergency hospitals on the day the first cases were announced and in the weeks that followed, supplemented the state’s ban on public gatherings with orders to close schools and places of worship.

Krusen commandeered a City Hall telephone exchange to coordinate hospitals and law enforcement, and enlisted thousands of nuns from the Archdiocese of Philadelphia as medical volunteers. Once the critical phase of the pandemic had passed, he steered the city’s efforts towards research into the disease.

A graduate of the Class of 1920 remembered:

“The appeal of Dr. Krusen for aid met with a magnificent response from the physician, nurse and pharmacist. Then it was that the pharmacist was lifted from the sordid plane of the business man to that of the self-sacrificing member of a profession whose doctrine is service to suffering humanity, no less than that of a physician and nurse. There was no talk of fancy salaries then. All leaped as one into the gap and labored with scarcely any rest to minister to the needs of the people. To those that fell ill in the struggle we yield them the silent homage that the living pay to the heroic dead.”

Citations:

“Enlisted Man Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 2, 1918.

“Classes to Go On,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 26, 1918.

England, Joseph, ed. The First Century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1821-1921. Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1922.

Higgins, Jim. An Epidemic’s Strawman: Wilmer Krusen, Philadelphia’s 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic, and Historical Memory, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 144, no. 1, 2020, pp. 61-88.

National Association of Retail Druggists. National Association of Retail Druggists Journal, vol. 27, 1918, p. 16.

Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. The Graduate: 1919, Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1919.

Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. The Graduate: 1920, Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1920.